Posted in: Sparks - Ideas, connecting the dots

Small tools for shaping

By Ryan Singer •

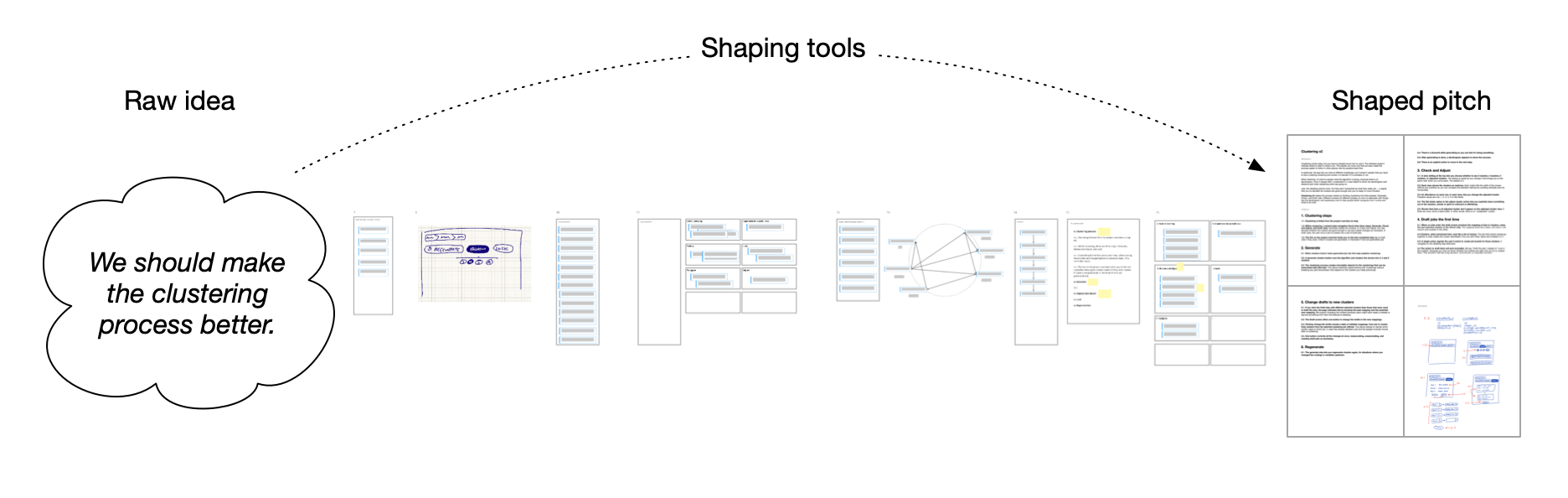

I'm experimenting with ways to demonstrate the path from a raw idea to a well-shaped pitch. That is, how to go from "I think we should spend time on X" to "here's a specific concept for X that we're confident we can ship in six weeks."

Sometimes I have a clear concept in my head from the very beginning, and I just need to sketch it out and write it up. Other times, it's more of a struggle. A project I just finished was one of those harder cases.

To get through it, instead of just staring at a blank page, I opened up a Miro board. My idea was to externalize my thought process by making small steps in a horizontal chain.

Along the way, I reached for a handful of small shaping tools. They allowed me to show steps that I would have otherwise done on a whiteboard or in my head. Some of them are from Shape Up (like fat marker sketching). Others are techniques I learned from Bob Moesta and Greg Engle at Re-Wired.

Tools used:

- TRACE

- DUMP

- AFFINITIZE

- CONTRAST

- SKETCH

- INTERRELATE

- MOCK

- SPIKE

This post will give you a tour of these tools and show how I used them to shape a real project.

The project

This project is one of the final cycles of an app I'm building with Bob and Greg to analyze and cluster demand-side interview data. Here's a screenshot of the work in progress:

All of these steps are built and working. The problem is that the clustering process in step four is confusing. It works, functionally, but it's very "power user" — you have to know a lot of things in your head and manipulate a lot of controls on the same screen that aren't well explained.

We agreed that if we could somehow "make clustering better" in six weeks, it would be time well spent. But that's too fuzzy to just start working on. I needed to shape that raw idea into some kind of specific project we could go do.

What is "better"?

I understood the current clustering UI was unclear. But I didn't have any ideas coming to mind for how to do it differently. I didn't understand what "better" should actually look like.

When this happens to me, sometimes I reach for a tool I'm calling TRACE. It's a technique to turn a fuzzy sense that something is wrong into specific focal points.

- First I observe somebody using the thing for a real purpose (or get a recording or interview them).

- Then I note every single step they took, from start to finish, including steps outside the tool. Eg. the timeline includes when they needed to switch to a different app, or Google a question, or apply a workaround.

- Any time they veer off the golden path and apply a compensating behavior, I flag that. This (a) indicates a problem, and (b) the compensating behavior shows what a solution could look like.

- I collect those flagged areas as the starting point for the design work.

I had recently done a real interview project with the app, and I recorded my screen as a friend and I went through the clustering steps. With the video at the ready, I opened Miro and created a long vertical box. As the video played, I dropped a card in the box to describe each step we performed. When something went wrong, I added a red sticky note to call it out. At the end I had five specific problems to focus on, which I collected as cards in another box.

"I need to get these out of my head"

As soon as I saw the specific problems, lots of different solution ideas started popping into my brain. I didn't want to slow down and start writing any one of them in detail because I was afraid I would lose the whole bunch. So I reached for a tool I affectionately call the DUMP.

A dump is just a box where I tell myself "you can put anything here without worrying if it's right or not." Importantly, there is no structure and no relationships. Just one column, and things go in one after the other.

In Miro, I made a box for the dump and got everything out of my head.

Now I'm glad I have some solution ideas. But since I was dumping everything out of my head without organizing it, I had a new problem. Now I felt like I was in the weeds with a lot of different details in front of me. Are these nine things I just wrote down really nine different things? Or do they boil down to a few major changes?

What goes together?

Whenever I have too many small things, I reach for AFFINITIZE. This is a chunking exercise that puts like with like, so you can go from many small things to a few big things. The secret to affinitizing is started with a fixed number of unnamed groups. Then, only after you've grouped things together, you look at the piles to understand what to call them.

I took the DUMP of solution ideas as the input to AFFINITIZE. I set up some empty boxes and dragged things one by one, until the copy of the dump was empty. Items that were closely related or affected the same part of the app went together.

After the items were grouped, I gave them names.

Now I had five big parts of the solution that were meaningfully different from each other. The first four were clear in my head — I knew how to take them forward. But the last one, named "Detail in bulk?" was half-baked and unclear. It had something to do with turning a one-by-one process into a single action, but I wasn't sure what I meant by it other than that.

Hm... I need options

Sometimes when I don't know how to go forward on something, I use a counterintuitive technique from Bob. It can actually be easier to come up with three ways to do something instead of just one way. That's because when you make three options, you can allow yourself a bad option. Articulating what doesn't work can actually spark new ideas simply by contrast.

So I'm calling this tool CONTRAST in this post. To do it, I draw three boxes side by side for three options, and allow myself to put anything I can think of in one of them. Often just asking myself "what would be a different approach than that?" will spark different approaches, and one of them might work.

I made three boxes in the Miro board. Two of the options were different ways to continue with a "detail" feature we already had in the app. But for the third option, I asked myself ... what if we reconsidered "detailing" as "locking" the clusters?

I thought to myself: "This option C is promising. Can I spell it out in more detail?" To do that, I added another dump to the chain.

Targeted sketching

That dump included an idea to make "lock" a separate phase of the clustering process, after "generate" and "review." This gave me the idea of a "step navigator" UI element that would structure the whole clustering process into three stages. This could be the centerpiece of the new approach. To see if it would work as I imagined, I reached for a tool everyone knows: SKETCH. I sketched an idea in Notability and pasted it in.

Note: When I think of SKETCH as a tool, it's differently from normal sketching. I'm not sketching everything. I'm tactically making a specific sketch to answer a specific unknown, get confidence, and then continue on with other work.

After sketching the three-part navigation structure, all the five parts of the feature I had listed earlier clicked together. It felt like a whole now. I could hang all the changes off of this idea. Now I felt ready to try and package this into a pitch to show other people.

Writing without writing

The problem is, a pitch is a written document. I wasn't ready to write yet. But I could see all the parts of the pitch in my head. So instead of going down into the weeds of writing, I created another dump and put all of the ingredients of the pitch into it.

Now I had all the elements of the pitch. But I still wanted to some stair-steps down from the fast and abstract level to the hard work of writing prose. The format I use for pitches uses top-level sections. I could AFFINITIZE this dump of patterns into sections of the pitch.

Now I could see six sections for the pitch, with elements belonging to each. The last question before I started writing was: What order should they go in? Where do I start? It's important that the pitch has a kind of "guided tour" quality to it, where one thing builds on the next, so that people who read it see the whole at once.

What goes first?

When I have a sequencing question, I reach for INTERRELATE. This tool draws out the causal dependencies between parts, so you see which ones should be upstream from the others. While it looks kind of technical, I think it captures what an expert does in their head when intuitively deciding which problems to solve first.

INTERRELATE starts with taking a set of input elements and arranging them around a circle. Then you draw an arrow from one element to another if doing that thing will help you do the other. After all the arrows are drawn, you can count the inputs vs. outputs at each element to judge which things have are causes of the rest of the system versus which things are more effects of the rest of the system. Things with more outputs than inputs should happen earlier in development.

I took the named groups from the latest AFFINITIZE as inputs to INTERRELATE. In this case, I asked myself whether explaining one element in the pitch would make it easier to explain another when drawing the arrows.

This confirmed my guess that "Navigate" should go first. Explaining navigate would let me touch on all the parts of the system before diving down into details about each later on.

Now I was ready to write. You might be noticing a pattern: I try to do as much pre-work as possible before I actually write anything because writing is really hard. I took the smallest possible step next. I ported each of those affinitized groups, now sequenced, into headlines. And I wrote out the first section in prose.

With the first section written, and the others stubbed out, the next task was to detail the rest. Again, I hesitated to go into writing mode. Couldn't I save myself some work by referencing the child elements in the affinitized groups? I copied the affinitized groups over, updated them to reflect a change I made in the first written draft. Then I could copy all the elements inside each box as outline points within the sections of the pitch.

At this point, I had to finally start writing. But I had a lot of guidelines in place to make it less daunting of a task. I went in and replaced the outlined points one by one with elaborated explanations.

A problem spot

Everything up to the final section was looking good. But trying to write the "Lock" section revealed to me that I hadn't fully thought it through. I was going to have to unpack what the actual solution involved some more before I could write it. I did have some ideas in my head, so I reached for a dump to list them out.

The ideas in the dump looked promising enough, but I didn't trust them without drawing some sketches so I could imagine the states of the UI more clearly.

Now I had more details to put into the pitch under the Lock section. But there was a gap between what was in the sketches and in my head and the precision a written pitch requires. So as a faster first step, I copied over the affinitized groups again and populated the Lock section with the new elements.

Now with all the new Lock mechanics out of my head, I felt comfortable slowing down and writing them into the pitch.

That "moment of truth" feeling

At this point I thought I was nearly done. But being almost done can trigger a "moment of truth" feeling about lingering problems. The whole time, I had a nervous feeling that the word "Lock" wasn't right. I called Bob to get his take, because he'd been using the app with clients and might have perspective.

He told me that not only was "lock" too final and anxiety-producing (for domain-specific reasons), but in some situations people would need to repeatedly "unlock" and iterate on the clusters.

I wasn't sure how to proceed. I needed a different approach for the Lock step and I didn't know what it was. So I reached for CONTRAST again and tried to fill in three wildly different solutions.

Dipping into the concrete

It helped. One of the ideas was to rethink of "locking" as turning the clusters into "draft jobs." The idea of "drafting" better fit the reality that selecting clusters was iterative, not always one-off. But I wasn't sure if that language would translate well into the UI. To put myself into the shoes of someone using the flow, I decided to MOCK instead of sketch the screens. A mock is more concrete than a sketch. The more doubts I have, the more concrete I need to be.

Mocking up the screens validated that the "draft" approach could work. But getting concrete helped me to see some problems I missed at the abstract level. In particular, changing the clusters after the fact was going to screw up some data in a downstream step. First I slowed down and restated the problems.

Concentrating on those specific problems helped me picture a solution idea. We could change the way we model the clusterings in the DB so they are easier to change. The refactoring had a few parts to it, so first I dumped it to get it out of my head.

Spiking to gauge risk

The next question was — is this code change really viable? I wouldn't want the whole pitch to depend on a refactoring that turns out to be a rabbit hole. To verify that it's a straight shot, I did a SPIKE. This is a term borrowed from Extreme Programming. It means a quick technical effort where you learn what's involved in a task by trying to do it. When I'm spiking, I'm mostly trying to verify that the task has a stopping point. If I keep finding other things that have to change, and more and more ripple effects, that tells me the change isn't going to be viable.

The spike involved sketching a schema change and looking at existing code to verify it would be compatible. Fortunately the spike showed the work to be a straight shot. Again, I updated the affinitized groups to quickly capture the changes before touching the pitch.

Using the affinitizer like a map, I found each part of the pitch that needed to change and rewrote it as needed.

Finishing up

Now that the content of the pitch was settled, I could format it. I number the parts of a pitch so they're easy to refer to, and that numbering is annoying to do when parts are still moving around.

Now that the patterns in the draft are numbered, I can create the example sketches I put on my pitches that show how the patterns could possibly combine into one feasible design.

Those go on the bottom of the pitch.

Then the final step is writing the motivation. The motivation is a section at the top of the pitch that summarizes why we're doing this, what problems we're trying to solve, and why they matter. This helps to energize the team that takes over the work and also give them information they need to make trade-offs and cuts if needed.

Again, writing is hard, so I first just dumped the key points the motivation should cover.

Then I wrote those points into prose as a standalone document.

And finally I prepended the motivation to the rest of the pitch.

Here's what the pitch looked like in the end:

Reflections

Showing my work as I shaped this project helped me to see some things.

First, there's a difference between a process and a toolbox. There's no "right order" for applying these tools. They don't make up a process. Each tool is a small thing used in a response to a specific challenge in a specific moment.

Second, while the order can look kind of random, there was continuity. I'm not sure yet, but I suspect that continuity from step to step distinguishes this work from "UX theater" where there are a lot of sticky notes and diagrams but no clear thread running through them all.

Finally, the chain didn't become exclusively more concrete over time. It didn't start in words and end in mock-ups. There were sketches, mockups, and code spikes along the way, but they appeared in the middle of the process to resolve specific questions. When the level of abstraction dipped down to resolve a doubt, it climbed again afterward, and in the end the pitch had the latitude it should so the development team can still determine the final form.